Stem Cell-based Therapies for Lyme Disease

at ANOVA IRM in Offenbach, Germany

Lyme Disease (LD) can potentially affect everyone, since it is transmitted by ticks which live in our temperate latitudes. It is a disease with many faces and can be associated with various symptoms, making the disease difficult to diagnose. In most cases, as soon as the disease is detected, a therapy with antibiotics is enough to cure the symptoms without residual impairments. But in some cases, especially if LD is diagnosed in progressive stages or in case of a chronic LD, an antibiotic therapy is insufficient and leaves the patient in pain or paresis.

An encouraging approach in treating LD are Stem Cell-based therapies, especially for patients who do not benefit from an antibiotic treatment. New studies have shown a significant improvement of the outcome in patients treated with Stem Cell-based therapies for Lyme Disease.

On this page we inform you about Lyme Disease covering an overview on important aspects of causes and symptoms, treatment options, precision diagnostics that reveals the cause of joint pain as well as our stem cell-based therapies that we offer in Offenbach (near Frankfurt/Main) Germany.

Jump directly to the following topics:

- What is the cause of LD?

- LD symptoms, stages, medication

- ANOVA therapies for LD

- Workflow of the treatment process

- Expectations and limits

- Diagnostics of pain-causing defects

- FAQ- frequently-asked questions

What is the Cause of Lyme Disease?

Lyme Disease (LD) or Borreliosis is a disease which can affect many different organs and systems, which makes treatment planning very difficult. It is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted by ticks. However, not all people bitten by an infected tick will get the disease. In most cases the infection is sub-clinical and without, or only with local symptoms. Yet in cases the infection gets disseminated, there is a large range of symptoms a patient may suffer from.

What is Lyme Disease?

LD - PTLDS - Meningitis - Symptoms - Medication

The disease proceeds in three stages. In stage I, which occurs in days to weeks after a bite, 50% of patients notice an itching, a red circle around the bite, the Erythema migrans. In many patients this is the only symptom of the infection and there will not be more manifestations. Sometimes this skin condition is accompanied by fatigue, lymph adenosis, headache, joint pain and fever.

Stage II is the early onset dissemination stage, which occurs weeks to months after the bite. Many patients cannot remember to be bitten by tick or suffering from an erythema, thus sometimes patients notice the infection only in stage II. Stage II comes with different symptoms in different systems. 3-12% of patients with Lyme Borreliosis suffer from an acute neuroborreliosis with Bannwarth-syndrome, which is characterized by severe radicular pain and paresis. Neuroborreliosis may also result in a lymphocyte meningism. Another organ which may be affected by Borreliosis is the heart. This so called Lyme-carditis comes with thoracic pain, dyspnoea and arrythmias.

Stage III is the late disseminated infection and occurs months to years after the bite. The patients suffer from Lyme-arthritis with pain and arthritis in large joints, often in the knees. Also, the neuroborreliosis may occur as a chronic form with progressive encephalitis and impairment of walking, cognition and bladder function.

Lyme disease is a disease with many faces, since it can include none of the mentioned symptoms, only some, or even all of them. Additionally, the outcome of the disease varies from a sub-clinical course, over no remaining symptoms, to significant remaining impairment after the infection. These various faces make the diagnosis and the treatment of Lyme Disease very difficult.

The major type of treatment is using antibiotics, in severe cases or late cases paralleled by neuroborreliosis applied intravenously.

Stem Cell Treatments for Lyme Disease at

ANOVA Institute for Regenerative Medicine - Offenbach, Germany

BMC and Secretome/Exosomes

Potency Hypothesis of Stem Cell Therapies

Stem cells possess the potential to communicate with the immune cells that elicit the inflammation and by natural, so far not understood mechanisms may inhibit this immune-over-reaction. Furthermore, stem cells have the ability to stimulate regeneration of tissue. The aim of a stem cell treatment is therefore, the fast relief of pain, the slowing of the disease progression and in the best cases to even support tissue regeneration. This can dramatically increase the quality of life, especially for patients with severe pain.

MSEC - Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome - Exosomes - Autologous

Patients with chronic inflammatory symptoms such as in LD are usually treated with MSEC (secretome, exosomes, EVs) of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC, AD-MSC, adipose-derived, fat-derived stem cells) which we harvest from the patients belly in a mini-liposuction (very brief and limited liposuction) under slight sedation. Worldwide, ANOVA is the first stem cell clinic to acquire legal permission form the responsible governmental authorities and therefore, offers high quality, safe and legally-controlled autologous (own) exosome-containing secretome.

The main advantage of MSEC is that in contrast to live stem cells, which would loose their therapeutic potency, can be frozen without loss of exosomes. This enables us to produce 10-20 injection doses from one liposuction which can then be administered over a longer treatment period. This is especially advantageous for serious cases of Lyme Disease. What a Secretome/Exosome is and how they compare is explained on our overview page.

BMC - Bone Marrow Concentrate - Autologous

Autologous (self) BMC are the second stem cell therapy that we use for treatment of Lyme Disease. However, BMC is a one-injection per bone marrow donation treatment.

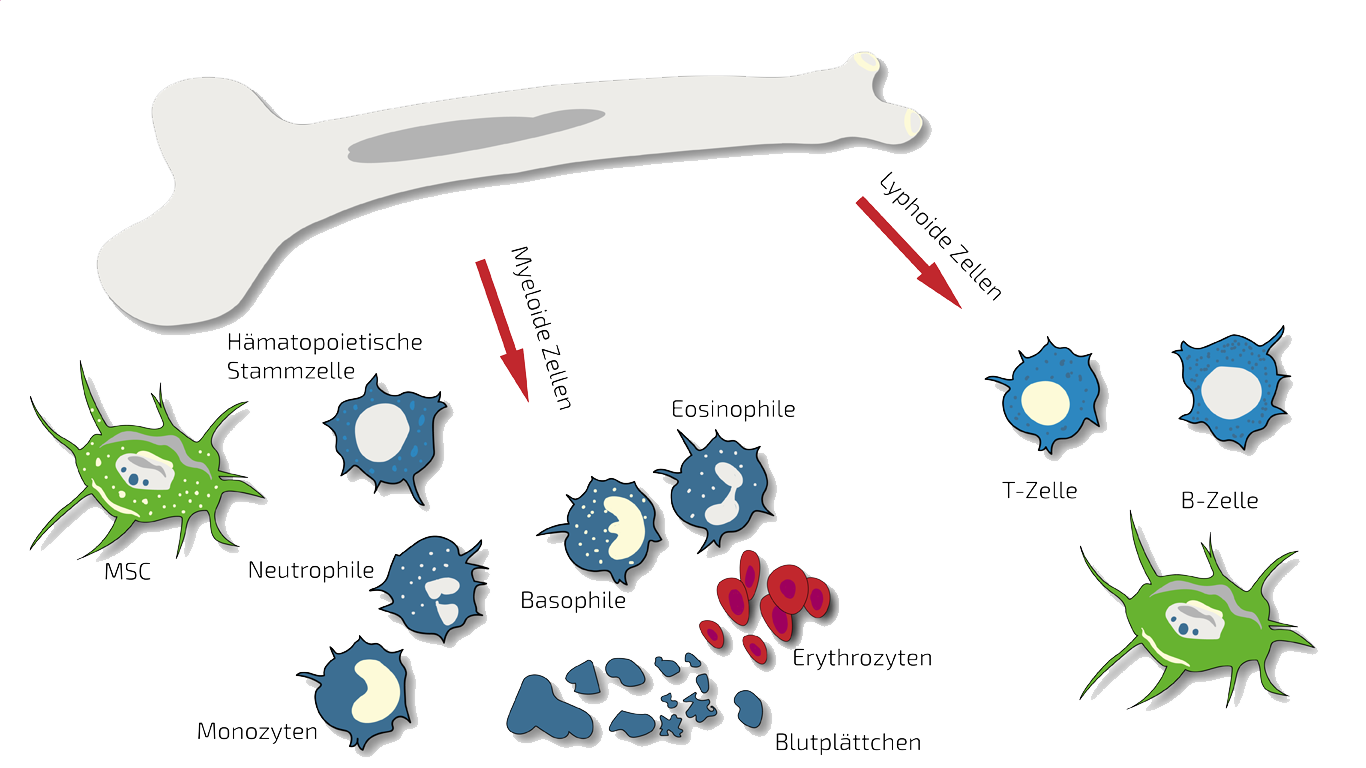

BMC contains autologous meaning patients own, adult stem cells (hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells in natural composition) which we isolate and concentrate from your pelvis crest in a short process under slight sedation.

These stem cells are supposed to inhibit the inflammation thereby relieving you from pain and to stimulate regeneration. For an on-going therapy, BMC treatments can be repeated or combined with MSEC treatment.

More information about this type of stem cell therapy is summarized on our page an BMC.

Contraindications

Our stem cell treatments are experimental, but we only treat patients for whom we believe the risk/benefit ratio indicates treatment based on the state of the art, i.e., medical, scientific evidence.

Please understand that we therefore do not treat patients for whom the following points apply:

- Active cancer in the last two years

- Not yet of legal age

- Existing pregnancy or lactation period

- Unable to breathe on own, ventilator

- Difficulty breathing in supine position

- Dysphagia (extreme difficulty swallowing)

- Psychiatric disorder

- Active infectious disease (Hepatitis A, B, C, HIV, Syphilis, or other)

Therapy Workflow for Lyme Disease

The precise workflow is described in detail on the stem cell- specific pages of BMC (most often used for LD) and Secretome/Exosomes.

All therapies are divided into phases such as evaluation of the medical history (we analyze your current therapies and medical records), initial counselling and evaluation of potential, patient-individual benefit of a stem cell therapy (indication statement), preliminary examinations, diagnostics, consultation on all therapy options, preparation of an individual treatment plan including cost estimate, harvesting of tissue, production of the stem cell product, quality control of the product and application. There are two special features for osteoarthritis and arthritis patients. If your previous findings have not found the specific causes of your joint pain, we will examine you in advance with a precise and informative arthro-MRI or an MRI with non-radioactive contrast medium, if you wish. In addition, we often apply the stem cells (BMC) intra-articularly (i.e., directly in the joint). This means that we deliver the stem cells to the exact location where your pain originates.

Unfortunately, according to the risk-benefit ratio, we cannot treat children or pregnant women. In addition, other factors can also be exclusion criteria.

How Long Does a Stem Cell Therapy Take?

The initial analyses and counselling can be done without you having to travel to Offenbach (near Frankfurt/Main, Germany). This period can be 2 weeks up to months depending on the availability of patients slots. If you live further away, we will conduct the initial discussions by telephone or video conference. For the actual treatment, you will travel to Offenbach. Then, depending on the therapy, the tissue collection, quality control and treatment type it will take as follows:

BMC-Therapy

Each donation and application of BMC on-site period: 2 days (consecutive days).

Secretome/Exosome-Therapy:

Preparation and harvest of the fat (mini-liposuction) need once 2 days (consecutive days) in Offenbach, followed by enrichment of the mesenchymal stem cells (secretome/exosomes) and quality control. Approximately 4 weeks after the isolation, the therapy begins according to the therapy plan determined with you. You will then come to Offenbach am Main (Germany) several times for the application. The shelf life of the secretome (exosomes) is 2 years.

How Much Does Stem Cell Treatment Cost?

Our treatments are always tailored to your specific situation, disease, stage and other factors. The therapies differ in the product used (BMC, secretome, PRP or hyaluronic acid), the frequency of treatment as well as the further examinations and your sedation and anesthesia wishes. A treatment for osteoarthritis and arthritis can cost from a few thousand to several thousand euros. You will receive a cost estimate for all treatments in advance so that you can accurately estimate what a treatment would cost in your individual case.

Does my Health Insurance Cover the Therapy Costs?

Unfortunately, at the moment it is assumed that health insurance companies do not cover the costs of experimental therapies (BMC, secretome, PRP, micro-fracture technique), i.e. you will have to bear the costs entirely yourself.

How Does the ANOVA Therapy Differ?

Diagnostics – We Look for the Cause of your Pain

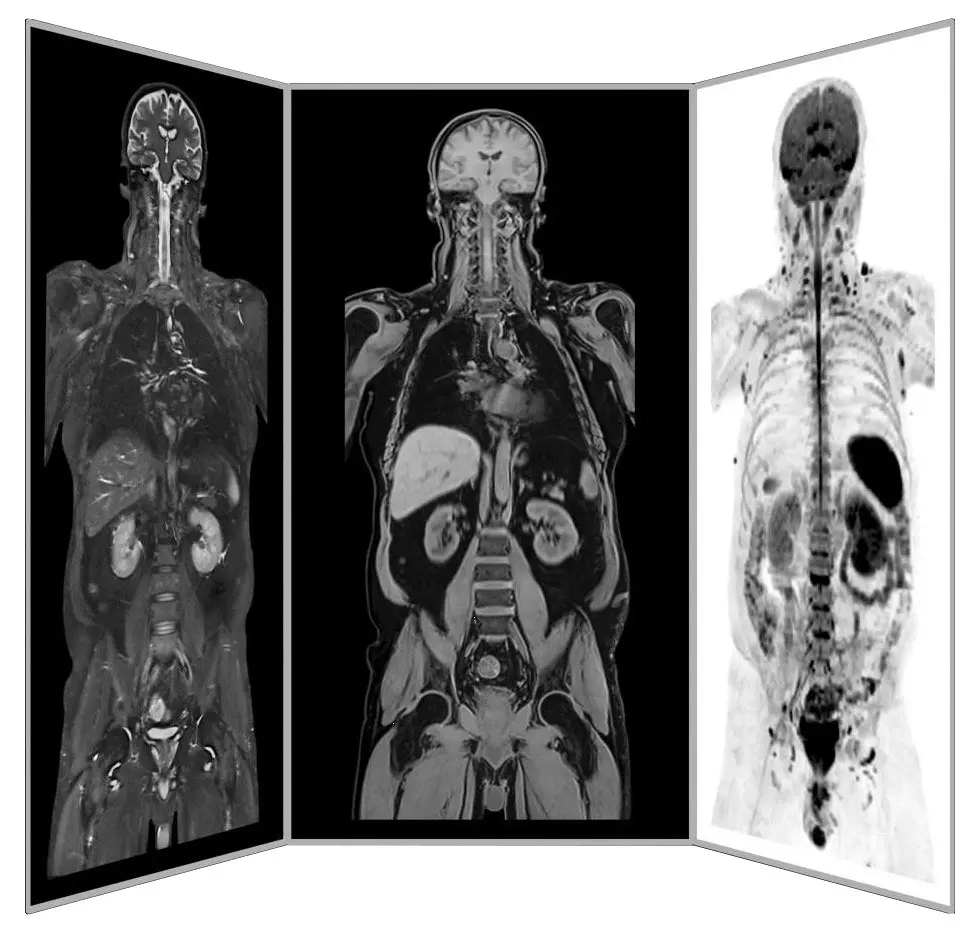

Dr. mult. Michael K. Stehling, the founder of ANOVA IRM and the Vitus Prostate Center , is a radiologist (MD) and holds a PhD in physics. For this reason, the ANOVA Institute for Regenerative Medicine, in cooperation with the Prof. Stehling Institute for Diagnostic Imaging located in the same building, has the capability to use special precision diagnostics such as arthro-MRI and non-radioactive contrast MRIs.

Compared to many conventional MRIs, these methods are often able to localize the pain-causing inflammation in your joints. This enables us to determine individually how patients should be treated and where the stem cells should be applied.

Furthermore, in consultation with you, we supplement our patient-specific diagnostics with specific blood tests on hormones, inflammation parameters and other factors that are important in your case, or recommend further examinations such as a preventive MRI spinal scan.

Precision MRI scans - find the source of pain

ANOVA IRM © Siemens Healthcare GmbH

How Stem Cells Can Help Treating Lyme Disease

Recent studies have shown a significant improvement for LD patients treated with Stem Cell-based therapies. While an antibiotic therapy is mostly successful in early stages of the acute form, this treatment is often insufficient in chronic LD, leaving the patients with impairments or pain. In those studies people with chronic LD regained their balance, appetite and strength and reduced tremor and other neurological symptoms.

Since LD is an inflammatory process, Stem Cell-based therapies can help to reduce the effect on the body, resulting in reduced symptoms and a better treatment outcome, especially when combined with other treatment options.

Treating Lyme Disease with MSC Secretome - Exosomes

Since LD is a disease with many faces and various symptoms, no patient is like the other. Therefore, no treatment should be like the other. At ANOVA, a German clinic for regenerative medicine, we evaluate the medical history of every patient and develop the therapeutic strategy that is best suited for the patient’s specific symptoms and manifestations.

ANOVA combines state-of-the-art technology with evidence-based effective therapies to treat every patient with a fitting treatment for the most effective outcome. This approach is one of a kind in Europe.

Stem Cell Secretome has anti-inflammatory properties that can help manage LD symptoms and facilitate the healing process of your body. Here you can read more about Stem Cell Secretome.

It should be noted that novel and/or experimental therapies, such as stem cell-based therapy, have not undergone the full clinical evaluation yet. Therefore, the attending physician is obliged to analyze the risks and benefits associated with stem cell therapy for each individual patient and case. If the benefits outweigh the potential risks, the doctor may suggest experimental therapies to the patient. Find out if you are suitable for stem cell therapy by contacting us today.

FAQ: Stem Cell-based Therapies for Lyme Disease

What are the Causes of Lyme Disease?

Lyme Disease is a disease caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. The bacteria are transmitted by ticks (Ixodes) endemic in temperate latitudes of the northern hemisphere. The risk of tick bites is increased during the warm months of March to October. It is important to note that not all people bitten by an infected tick will develop the disease. But still it is important to watch out for the first symptoms of an infection to get early treatment.

Since the bacteria are in the gut of the tick, the risk of an infection increases with the time the tick is attached to the skin. An early removal of the tick is a good prevention of getting LD.

Since there is no vaccination against Borrelia burgdorferi yet, the best prevention is to avoid bites and to remove ticks as soon as possible.

What are the Symptoms of Lyme Disease?

As mentioned above, LD comes with various manifestations, depending on the stage. Keeping in mind that every patient is different and the range is wide, it is also important to note that it’s possible to suffer from none of those symptoms to all of them. There are also some symptoms that are rare, but potentially possible, such as hepatitis or conjunctivitis. Nevertheless, there are characteristic symptoms for every stage.

Stage I:

- Erythema migrans (most specific)

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Lymphadenosis

Stage II:

- Acute neuroborreliosis

- Headache

- Facial paresis

- Paresis of limbs

- Radicular pain, especially during the night

- Lyme-Carditis

- Arrythmia

- Dyspnoea

- Thoracic pain

Stage III:

- Lyme-Arthritis

- Joint pain

- Swollen joints

- Fatigue

- Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

- Progressive erythema on limbs, especially the lower legs

- Chronic neuroborrelioses

- Progressive encephalitis

- Impairment of bladder function, cognition and walking None of these symptoms is proof of Lyme Disease.

If there is a suspicion on an infection with Borrelia Burgdorferi, a precise diagnostic is urgently needed.

How is Lyme Disease Diagnosed?

Important in diagnosing LD is the evaluation of the medical history, to determine if a tick bite occurred. But even if there is no such incident known, it does not mean it is not LD. Often patients do not remember the bite or did not notice it. If the physicians have the suspicion because of the combination of symptoms, a blood test (sometimes cerebrospinal fluid is also needed) will be performed. The body produces antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi, which can be detected in the patient’s blood or cerebrospinal fluid. The combination of specific symptoms, no other explanation for the symptoms and a positive antibody-reaction will confirm the diagnosis.

What Other Treatments are Available?

As soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, a therapy with antibiotics is started. Which antibiotic is used depends on the stage and the symptoms of the patient.

Often, the medication will stop the infection and the symptoms will disappear. But sometimes, especially with acute or chronical neuroborreliosis, residuals as paresis are possible and are a large impairment of the patient’s quality of life.

In early stages of LD, the antibiotic therapy will cure the disease without residuals in most cases. But especially in advanced stages the risk of therapy-refractory courses increases.

References and Literature

If you are interested to receive the list of references, please contact us.

Further References for MSC, BMC, Stemcell Secretome and EVs

- Georg Hansmann, Philippe Chouvarine, Franziska Diekmann, Martin Giera, Markus Ralser, Michael Mülleder, Constantin von Kaisenberg, Harald Bertram, Ekaterina Legchenko & Ralf Hass "Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived treatment of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension". Nature Cardiovascular Research volume 1, pages568–576 (2022).

- Murphy JM, Fink DJ, Hunziker EB, et al. Stem cell therapy in a caprine model of osteoarthritis . Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3464–74.

- Lee KB, Hui JH, Song IC, Ardany L, et al. Injectable mesenchymal stem cell therapy for large cartilage defects—a porcine model. Stem Cell. 2007;25:2964–71.

- Saw KY, Hussin P, Loke SC, et al. Articular cartilage regeneration with autologous marrow aspirate and hyaluronic acid: an experimental study in a goat model. Arthroscopy . 2009;25(12):1391–400.

- Black L, Gaynor J, Adams C, et al. Effect of intra-articular injection of autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem and regenerative cells on clinical signs of chronic osteoarthritis of the elbow joint in dogs. Vet Ther. 2008;9:192-200.

- Centeno C, Busse D, Kisiday J, et al. Increased knee cartilage volume in degenerative joint disease using percutaneously implanted, autologous mesenchymal stem cells. Pain Physician. 2008;11(3):343–53.

- Centeno C, Kisiday J, Freeman M, et al. Partial regeneration of the human hip via autologous bone marrow nucleated cell transfer: a case study. Pain Physician. 2006;9:253–6.

- Centeno C, Schultz J, Cheever M. Safety and complications reporting on the re-implantation of culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells using autologous platelet lysate technique. Curr Stem Cell. 2011;5(1):81–93.

- Pak J. Regeneration of human bones in hip osteonecrosis and human cartilage in knee osteoarthritis with autologous adipose derived stem cells: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2001;5:296.

- Kuroda R, Ishida K, et al. Treatment of a full-thickness articular cartilage defect in the femoral condyle of an athlete with autologous bone-marrow stromal cells. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:226–31.

- Emadedin M, Aghdami N, Taghiyar L, et al. Intra-articular injection of autologous mesenchymal stem cells in six patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(7):422–8.

- Saw KY et al. Articular cartilage regeneration with autologous peripheral blood stem cells versus hyaluronic acid: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):684–94.

- Vangsness CT, Farr J, Boyd J, et al. Adult human mesenchymal stem cells delivered via intra-articular injection to the knee following partial medial meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 2014;96(2):90–8.

- Freitag, Julien, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in the treatment of osteoarthritis: reparative pathways, safety and efficacy–a review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 17.1 (2016): 230.

- Maumus, Marie, Christian Jorgensen, and Danièle Noël. " Mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine applied to rheumatic diseases: role of secretome and exosomes. " Biochimie 95.12 (2013): 2229-2234.

- Dostert, Gabriel, et al. " How do mesenchymal stem cells influence or are influenced by microenvironment through extracellular vesicles communication?. " Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 5 (2017).

- Chaparro, Orlando, and Itali Linero. " Regenerative Medicine: A New Paradigm in Bone Regeneration. " (2016).

- Toh, Wei Seong, et al. " MSC exosome as a cell-free MSC therapy for cartilage regeneration: Implications for osteoarthritis treatment. " Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. Academic Press, 2016.

- Chaparro, Orlando, and Itali Linero. " Regenerative Medicine: A New Paradigm in Bone Regeneration. " (2016).

- S. Koelling, J. Kruegel, M. Irmer, J.R. Path, B. Sadowski, X. Miro, et al., Migratory chondrogenic progenitor cells from repair tissue during the later stages of human osteoarthritis , Cell Stem Cell 4 (2009) 324–335.

- B.A. Jones, M. Pei, Synovium-Derived stem cells: a tissue-Specific stem cell for cartilage engineering and regeneration , Tissue Eng. B: Rev. 18 (2012) 301–311.

- W. Ando, J.J. Kutcher, R. Krawetz, A. Sen, N. Nakamura, C.B. Frank, et al., Clonal analysis of synovial fluid stem cells to characterize and identify stable mesenchymal stromal cell/mesenchymal progenitor cell phenotypes in a porcine model: a cell source with enhanced commitment to the chondrogenic lineage, Cytotherapy 16 (2014) 776–788.

- K.B.L. Lee, J.H.P. Hui, I.C. Song, L. Ardany, E.H. Lee, Injectable mesenchymal stem cell therapy for large cartilage defects—a porcine model, Stem Cells 25 (2007) 2964–2971.

- W.-L. Fu, C.-Y. Zhou, J.-K. Yu, A new source of mesenchymal stem cells for articular cartilage repair: mSCs derived from mobilized peripheral blood share similar biological characteristics in vitro and chondrogenesis in vivo as MSCs from bone marrow in a rabbit model , Am. J. Sports Med. 42 (2014) 592–601.

- X. Xie, Y. Wang, C. Zhao, S. Guo, S. Liu, W. Jia, et al., Comparative evaluation of MSCs from bone marrow and adipose tissue seeded in PRP-derived scaffold for cartilage regeneration , Biomaterials 33 (2012) 7008–7018.

- E.-R. Chiang, H.-L. Ma, J.-P. Wang, C.-L. Liu, T.-H. Chen, S.-C. Hung, Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells in combination with hyaluronic acid for the treatment of osteoarthritis in rabbits , PLoS One 11 (2016) e0149835.

- H. Nejadnik, J.H. Hui, E.P. Feng Choong, B.-C. Tai, E.H. Lee, Autologous bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells versus autologous chondrocyte implantation: an observational cohort study , Am. J. Sports Med. 38 (2010) 1110–1116.

- I. Sekiya, T. Muneta, M. Horie, H. Koga, Arthroscopic transplantation of synovial stem cells improves clinical outcomes in knees with cartilage defects , Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 473 (2015) 2316–2326.

- Y.S. Kim, Y.J. Choi, Y.G. Koh, Mesenchymal stem cell implantation in knee osteoarthritis: an assessment of the factors influencing clinical outcomes , Am. J. Sports Med. 43 (2015) 2293–2301.

- W.-L. Fu, Y.-F. Ao, X.-Y. Ke, Z.-Z. Zheng, X. Gong, D. Jiang, et al., Repair of large full-thickness cartilage defect by activating endogenous peripheral blood stem cells and autologous periosteum flap transplantation combined with patellofemoral realignment , Knee 21 (2014) 609–612.

- Y.-G. Koh, O.-R. Kwon, Y.-S. Kim, Y.-J. Choi, D.-H. Tak, Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells with microfracture versus microfracture alone: 2-year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial , Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 32 (2016) 97–109.

- T.S. de Windt, L.A. Vonk, I.C.M. Slaper-Cortenbach, M.P.H. van den Broek, R. Nizak, M.H.P. van Rijen, et al., Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells stimulate cartilage regeneration and are safe for single-Stage cartilage repair in humans upon mixture with recycled autologous chondrons , Stem Cells (2016) (n/a-n/a).

- L. da Silva Meirelles, A.M. Fontes, D.T. Covas, A.I. Caplan, Mechanisms involved in the therapeutic properties of mesenchymal stem cells , Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 20 (2009) 419–427.

- W.S. Toh, C.B. Foldager, M. Pei, J.H.P. Hui, Advances in mesenchymal stem cell-based strategies for cartilage repair and regeneration , Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 10 (2014) 686–696.

- R.C. Lai, F. Arslan, M.M. Lee, N.S.K. Sze, A. Choo, T.S. Chen, et al., Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury , Stem Cell Res. 4 (2010) 214–222.

- S. Zhang, W.C. Chu, R.C. Lai, S.K. Lim, J.H.P. Hui, W.S. Toh, Exosomes derived from human embryonic mesenchymal stem cells promote osteochondral regeneration, Osteoarthr . Cartil. 24 (2016) 2135–2140.

- S. Zhang, W. Chu, R. Lai, J. Hui, E. Lee, S. Lim, et al., 21 – human mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote orderly cartilage regeneration in an immunocompetent rat osteochondral defect model , Cytotherapy 18 (2016) S13.

- C.T. Lim, X. Ren, M.H. Afizah, S. Tarigan-Panjaitan, Z. Yang, Y. Wu, et al., Repair of osteochondral defects with rehydrated freeze-dried oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] hydrogels seeded with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in a porcine model

- A. Gobbi, G. Karnatzikos, S.R. Sankineani, One-step surgery with multipotent stem cells for the treatment of large full-thickness chondral defects of the knee , Am. J. Sports Med. 42 (2014) 648–657.

- A. Gobbi, C. Scotti, G. Karnatzikos, A. Mudhigere, M. Castro, G.M. Peretti, One-step surgery with multipotent stem cells and Hyaluronan-based scaffold for the treatment of full-thickness chondral defects of the knee in patients older than 45 years , Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. (2016) 1–8.

- A. Gobbi, G. Karnatzikos, C. Scotti, V. Mahajan, L. Mazzucco, B. Grigolo, One-step cartilage repair with bone marrow aspirate concentrated cells and collagen matrix in full-thickness knee cartilage lesions: results at 2-Year follow-up , Cartilage 2 (2011) 286–299.

- K.L. Wong, K.B.L. Lee, B.C. Tai, P. Law, E.H. Lee, J.H.P. Hui, Injectable cultured bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in varus knees with cartilage defects undergoing high tibial osteotomy: a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial with 2 years’ follow-up , Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 29 (2013) 2020–2028.

- J.M. Hare, J.E. Fishman, G. Gerstenblith, et al., Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: the poseidon randomized trial, JAMA 308 (2012) 2369–2379.

- L. Wu, J.C.H. Leijten, N. Georgi, J.N. Post, C.A. van Blitterswijk, M. Karperien, Trophic effects of mesenchymal stem cells increase chondrocyte proliferation and matrix formation , Tissue Eng. A 17 (2011) 1425–1436.

- L. Wu, H.-J. Prins, M.N. Helder, C.A. van Blitterswijk, M. Karperien, Trophic effects of mesenchymal stem cells in chondrocyte Co-Cultures are independent of culture conditions and cell sources , Tissue Eng. A 18 (2012) 1542–1551.

- S.K. Sze, D.P.V. de Kleijn, R.C. Lai, E. Khia Way Tan, H. Zhao, K.S. Yeo, et al., Elucidating the secretion proteome of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells , Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6 (2007) 1680–1689.

- M.B. Murphy, K. Moncivais, A.I. Caplan, Mesenchymal stem cells: environmentally responsive therapeutics for regenerative medicine , Exp. Mol. Med. 45 (2013) e54.

- M.J. Lee, J. Kim, M.Y. Kim, Y.-S. Bae, S.H. Ryu, T.G. Lee, et al., Proteomic analysis of tumor necrosis factor--induced secretome of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells , J. Proteome Res. 9 (2010) 1754–1762.

- S. Bruno, C. Grange, M.C. Deregibus, R.A. Calogero, S. Saviozzi, F. Collino, et al., Mesenchymal stem cell-derived microvesicles protect against acute tubular injury, J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20 (2009) 1053–1067.

- M. Yá˜nez-Mó, P.R.-M. Siljander, Z. Andreu, A.B. Zavec, F.E. Borràs, E.I. Buzas, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions (2015).

- C. Lawson, J.M. Vicencio, D.M. Yellon, S.M. Davidson, Microvesicles and exosomes: new players in metabolic and cardiovascular disease , J. Endocrinol. 228 (2016) R57–R71.

- A.G. Thompson, E. Gray, S.M. Heman-Ackah, I. Mager, K. Talbot, S.E. Andaloussi, et al., Extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative diseas—pathogenesis to biomarkers, Nat. Rev. Neurol. 12 (2016) 346–357.

- I.E.M. Bank, L. Timmers, C.M. Gijsberts, Y.-N. Zhang, A. Mosterd, J.-W. Wang, et al., The diagnostic and prognostic potential of plasma extracellular vesicles for cardiovascular disease , Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 15 (2015) 1577–1588.

- T. Kato, S. Miyaki, H. Ishitobi, Y. Nakamura, T. Nakasa, M.K. Lotz, et al., Exosomes from IL-1 stimulated synovial fibroblasts induce osteoarthritic changes in articular chondrocytes , Arthritis. Res. Ther. 16 (2014) 1–11.

- R.W.Y. Yeo, S.K. Lim, Exosomes and their therapeutic applications, in: C. Gunther, A. Hauser, R. Huss (Eds.), Advances in Pharmaceutical Cell TherapyPrinciples of Cell-Based Biopharmaceuticals, World Scientific, Singapore, 2015, pp. 477–491.

- X. Qi, J. Zhang, H. Yuan, Z. Xu, Q. Li, X. Niu, et al., Exosomes secreted by human-Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells repair critical-sized bone defects through enhanced angiogenesis and osteogenesis in osteoporotic rats , Int. J. Biol. Sci. 12 (2016) 836–849.

- R.C. Lai, F. Arslan, S.S. Tan, B. Tan, A. Choo, M.M. Lee, et al., Derivation and characterization of human fetal MSCs: an alternative cell source for large-scale production of cardioprotective microparticles , J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48 (2010) 1215–1224.

- Y. Zhou, H. Xu, W. Xu, B. Wang, H. Wu, Y. Tao, et al., Exosomes released by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells protect against cisplatin-induced renal oxidative stress and apoptosis in vivo and in vitro , Stem Cell Res. Ther. 4 (2013) 1–13.

- Y. Qin, L. Wang, Z. Gao, G. Chen, C. Zhang, Bone marrow stromal/stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles regulate osteoblast activity and differentiation in vitro and promote bone regeneration in vivo , Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 21961.

- M. Nakano, K. Nagaishi, N. Konari, Y. Saito, T. Chikenji, Y. Mizue, et al., Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve diabetes-induced cognitive impairment by exosome transfer into damaged neurons and astrocytes , Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 24805.

- K. Nagaishi, Y. Mizue, T. Chikenji, M. Otani, M. Nakano, N. Konari, et al., Mesenchymal stem cell therapy ameliorates diabetic nephropathy via the paracrine effect of renal trophic factors including exosomes , Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 34842.

- S.R. Baglio, K. Rooijers, D. Koppers-Lalic, F.J. Verweij, M. Pérez Lanzón, N. Zini, et al., Human bone marrow- and adipose-mesenchymal stem cells secrete exosomes enriched in distinctive miRNA and tRNA species , Stem Cell Res. Ther. 6 (2015) 1–20.

- T. Chen, R. Yeo, F. Arslan, Y. Yin, S. Tan, Efficiency of exosome production correlates inversely with the developmental maturity of MSC donor, J. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 3 (2013) 2.

- R.C. Lai, S.S. Tan, B.J. Teh, S.K. Sze, F. Arslan, D.P. de Kleijn, et al., Proteolytic potential of the MSC exosome proteome: implications for an exosome-mediated delivery of therapeutic proteasome , Int. J. Proteomics 2012 (2012) 971907.

- T.S. Chen, R.C. Lai, M.M. Lee, A.B.H. Choo, C.N. Lee, S.K. Lim, Mesenchymal stem cell secretes microparticles enriched in pre-microRNAs , Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (2010) 215–224.

- R.W. Yeo, R.C. Lai, K.H. Tan, S.K. Lim, Exosome: a novel and safer therapeutic refinement of mesenchymal stem cell, J. Circ. Biomark. 1 (2013) 7.

- R.C. Lai, R.W. Yeo, S.K. Lim, Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes, Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 40 (2015) 82–88.

- B. Zhang, R.W. Yeo, K.H. Tan, S.K. Lim, Focus on extracellular vesicles: therapeutic potential of stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles , Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 (2016) 174.

- Hu G-w, Q. Li, X. Niu, B. Hu, J. Liu, Zhou S-m, et al., Exosomes secreted by human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate limb ischemia by promoting angiogenesis in mice , Stem Cell Res. Ther. 6 (2015) 1–15.

- J. Zhang, J. Guan, X. Niu, G. Hu, S. Guo, Q. Li, et al., Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived MSCs facilitate cutaneous wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis , J. Transl. Med. 13 (2015) 1–14.

- B. Zhang, M. Wang, A. Gong, X. Zhang, X. Wu, Y. Zhu, et al., HucMSC-exosome mediated-Wnt4 signaling is required for cutaneous wound healing, Stem Cells 33 (2015) 2158–2168.

- B. Zhang, Y. Yin, R.C. Lai, S.S. Tan, A.B.H. Choo, S.K. Lim, Mesenchymal stem cells secrete immunologically active exosomes , Stem Cells Dev. 23 (2013) 1233–1244.

- C.Y. Tan, R.C. Lai, W. Wong, Y.Y. Dan, S.-K. Lim, H.K. Ho, Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote hepatic regeneration in drug-induced liver injury models , Stem Cell Res. Ther. 5 (2014) 1–14.

- C. Lee, S.A. Mitsialis, M. Aslam, S.H. Vitali, E. Vergadi, G. Konstantinou, et al., Exosomes mediate the cytoprotective action of mesenchymal stromal cells on hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension , Circulation 126 (2012) 2601–2611.

- B. Yu, H. Shao, C. Su, Y. Jiang, X. Chen, L. Bai, et al., Exosomes derived from MSCs ameliorate retinal laser injury partially by inhibition of MCP-1 , Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 34562.

- Jo CH, Lee YG, Shin WH, et al. Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a proof of concept clinical trial. Stem Cells. 2014;32(5):1254–66.

- Vega, Aurelio, et al. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: a randomized controlled trial. Transplantation. 2015;99(8):1681–90.

- Davatchi F, Sadeghi-Abdollahi B, Mohyeddin M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Preliminary report of four patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14(2):211–5

- Hernigou P, Flouzat Lachaniette CH, Delambre J, et al. Biologic augmentation of rotator cuff repair with mesenchymal stem cells during arthroscopy improves healing and prevents further tears: a case- controlled study. Int Orthop. 2014;38(9):1811–1818

- Galli D, Vitale M, Vaccarezza M. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cell differentiation toward myogenic lineages: facts and perspectives. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:6.

- Beitzel K, Solovyova O, Cote MP, et al. The future role of mesenchymal Stem cells in The management of shoulder disorders . Arthroscopy. 2013;29(10):1702–1711.

- Isaac C, Gharaibeh B, Witt M, Wright VJ, Huard J. Biologic approaches to enhance rotator cuff healing after injury. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(2):181–190.

- Malda, Jos, et al. " Extracellular vesicles [mdash] new tool for joint repair and regeneration. " Nature Reviews Rheumatology (2016).

Further References about PRP

- Rubio-Azpeitia E, Andia I. Partnership between platelet-rich plasma and mesenchymal stem cells: in vitro experience. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(1):52–62.

Extras

- Xu, Ming, et al. " Transplanted senescent cells induce an osteoarthritis-like condition in mice. " The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences (2016): glw154.

- McCulloch, Kendal, Gary J. Litherland, and Taranjit Singh Rai. " Cellular senescence in osteoarthritis pathology ." Aging Cell (2017).

Patient Services at ANOVA Institute for Regenerative Medicine

- Located in the center of Germany, quick access by car or train from anywhere in Europe

- Simple access worldwide, less than 20 minutes from Frankfurt Airport

- Individualized therapy with state-of-the-art stem cell products

- Individually planned diagnostic work-up which include world-class MRI and CT scans

- German high quality standard on safety and quality assurance

- Personal service with friendly, dedicated Patient Care Managers

- Scientific collaborations with academic institutions to assure you the latest regenerative medical programs